Discriminatory redistricting and representation

Gerrymandering, the manipulation of congressional redistricting for political gain, is another tactic that has long undermined the democratic process—particularly in the South, where it has been used to entrench white political power. Redistricting, the process of creating geographic boundaries of electoral districts, typically occurs every decade following the release of the Census. Since the founding of the United States, political parties vying for power frequently gamed the redistricting process to secure an electoral advantage (Engstrom 2013). And following emancipation and Black suffrage, Southern legislators regularly used discriminatory redistricting to suppress Black and brown voting power.

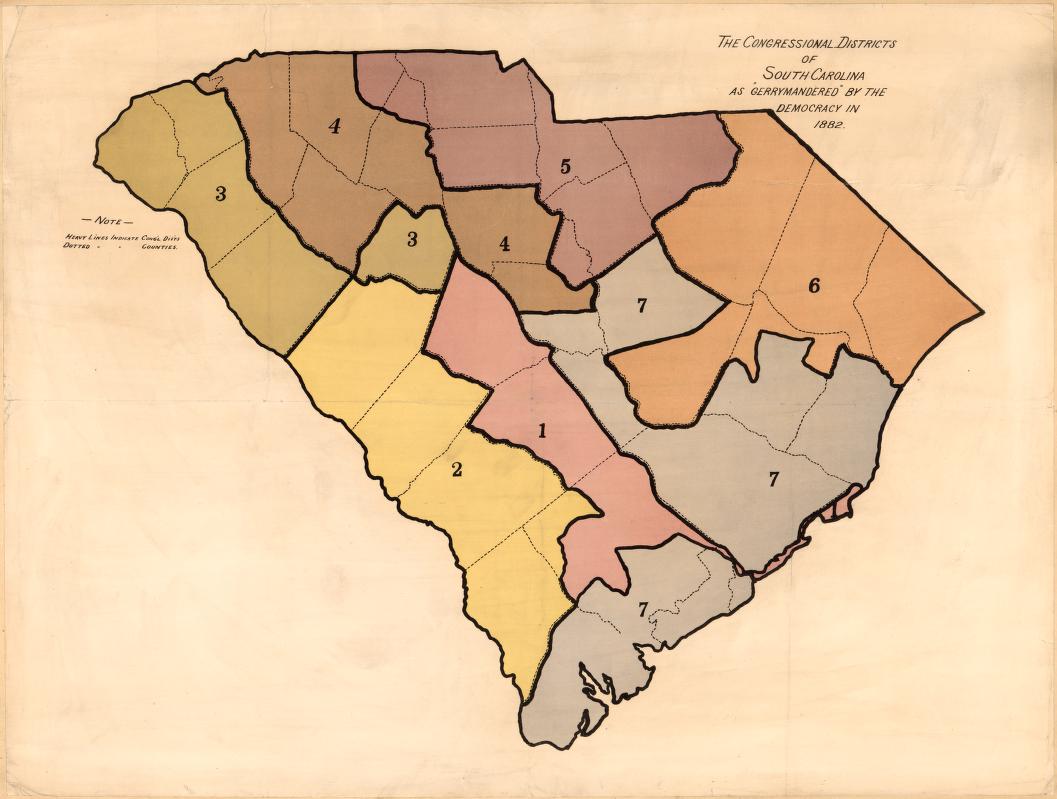

One of the most glaring historical examples of discriminatory racial gerrymandering is South Carolina’s 1882 “boa constrictor” district map, which created discontinuous boundaries, and aimed to stifle Black voter power by concentrating the state’s Black population into one district (LOC 1882).

Figure H. South Carolina’s 1882 “boa constrictor” congressional district map, which packed Black voters into one noncontiguous district (District 7) and diluted their power in all other districts. (LOC 1882)

The VRA of 1965 gave individuals the power to legally challenge racial gerrymanders. But to this day, Southern states continuously engage in discriminatory gerrymandering under the guise of partisan redistricting. Below are just a few examples of racial gerrymandering cases from recent years:

- In 2016, a federal court struck down North Carolina’s congressional map, ruling it an unconstitutional racial gerrymander aimed at diminishing the voting power of Black Americans.

- In 2017, a federal court ruled that several Texas congressional and state legislative districts were drawn with the intent of discriminating against Black and Latino voters.

- In 2020, South Carolina’s congressional map was deemed illegal by a federal court. An amicus brief alleged that South Carolina had purposefully drawn discriminatory districts that “bleached” Black voters out of select congressional districts in a manner that harkened back to the 1882 “boa constrictor” congressional district map. This ruling was later overturned by the Supreme Court in 2023.

- In 2022, a federal court struck down Alabama’s congressional map for diluting Black voters’ political influence by spreading them across multiple districts. After defying an order to create a second Black majority district, litigation in this case is ongoing (Li 2023).

Partisan actors have also attempted to manipulate the apportionment process by proposing changes to the way the population is counted (Rudensky et al. 2021). These efforts included proposals to add a citizenship question to the Census and to not count non-voting populations in apportionment. Experts predict that this approach would disproportionally target Latino communities (as well as Asian American and Black communities, to a lesser extent), which would clearly be a violation of the Census Act (Rudensky et al. 2021).

Despite the safeguards of the VRA, particularly Section 2 which prohibits voting practices with discriminatory effects, gerrymandering continues to undermine Black and brown voting power across the South.

Mass incarceration is a key tool for disenfranchising Black and brown voters

Felony disenfranchisement is a vestige of the racist backlash against emancipation and Reconstruction and remains a pervasive tool for suppressing Black and brown political participation in the South today. As Black Code laws laid the groundwork for mass incarceration by criminalizing Black freed men and women, states also enacted laws to strip voting rights from people convicted of felonies. Between 1865 and 1880, 13 states (Alabama, Arkansas, Colorado, Florida, Georgia, Illinois, Mississippi, Missouri, Nebraska, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, and Texas) either introduced or expanded felony disenfranchisement laws. Even as the VRA of 1965 undid many of the barriers to voting established by Black Codes and Jim Crow laws, 25 states still have some form of felony disenfranchisement in place (Brennan Center n.d.).

In recent years, states have increasingly prosecuted individuals for voting without realizing they were disenfranchised due to a felony conviction. In 2018, Florida voters passed Amendment 4 to reinstate voting rights to individuals with previous felony convictions. Florida Governor Ron DeSantis and the Florida legislature responded by passing Senate Bill 7066, which prohibited individuals with previous convictions from voting until they paid court-imposed fees (Brennan Center 2023). In 2022, footage was released showing individuals being arrested at gunpoint and charged with election fraud after having unknowingly voted without paying these court-ordered fees (Mower 2022).

Today, about 4.4 million Americans, roughly the equivalent of the entire voting population of the state of Minnesota, have their right to vote revoked because of a criminal conviction (Porter et al. 2024; USFR 2024). Because incarceration rates are still highly racialized, Black Americans are much more likely to be disenfranchised this way. In Southern states like Alabama, Florida, Kentucky, Mississippi, Tennessee, and Virginia, more than one in seven Black Americans are disenfranchised because of felony convictions—twice the national average (Uggen et al. 2020). Without efforts to undo this vestige of slavery, felony disenfranchisement will continue to exclude millions of primarily Black and brown citizens across the South from civic participation.

Preempting local governance

Preemption is a practice where state legislatures bar local governments from adopting rules or standards distinct from those set by the state government. Over the last half century, preemption has been increasingly employed by majority-white legislatures in the South and Midwest to block local governments’ ability to enact ordinances related to labor standards, voting rights, climate, public health, law enforcement, and other issues.

Notably, in 10 of the 11 former Confederate states, localities are preempted from enacting local minimum wage ordinances. By prohibiting cities and counties from raising wages, majority-white state legislatures maintain a labor market dependent on a cheap and precarious workforce—an enduring feature of the Southern economic development model (EPI 2024; Blair et al. 2020; Childers 2024b).

In recent decades, the use of preemption has accelerated, targeting pro-worker measures like pro-union legislation, project labor agreements, prevailing wage ordinances, paid sick leave, and even the removal of Confederate monuments (Blair et al. 2020). This model, rooted in the legacy of slavery and exploitation, relies on suppressing labor rights and keeping wages low to preserve the economic dominance of a select few.

Conclusion

The preservation of the Southern economic development model has depended on the systematic disenfranchisement of Black and brown communities since emancipation. From the abolition of slavery through Reconstruction, the Jim Crow era, and even the Civil Rights Movement, the cycle of progress and backlash is testament to how fiercely and relentlessly Southern white elites will use racism, violence, and political suppression to secure their economic interests. Every step towards Black political empowerment has been met with new forms of suppression, aimed at maintaining a system that relies on an exploited and disempowered workforce.

Although this legacy continues through tactics like gerrymandering, felony disenfranchisement, and local preemption laws, periods like Reconstruction and the Civil Rights Movement, show that targeted policy action can dismantle racist barriers to voting and political participation. Breaking this entrenched cycle will require sustained efforts to dismantle the dynamic of political suppression and economic exploitation. Further, without confronting these deeply rooted structures of exploitation and disenfranchisement in the South, these dynamics will continue to spread and undermine progress across the nation.

“If you don’t organize the South, the South will come to you”

—Willy Woods, Unite Here Local 23 Chapter President

Notes

Economic Policy Institute, “Rooted in Racism and Economic Exploitation” (web page).

Alexander v. South Carolina State Conference of the NAACP 2024; Brief of Amici Curiae Historians in Support of Appellees and Affirmance, Alexander v. South Carolina State Conference of the NAACP 2023.

Rucho v. Common Cause 2019.

Abbott v. Perez 2018.

Alexander v. South Carolina State Conference of the NAACP 2024; Brief of Amici Curiae Historians in Support of Appellees and Affirmance, Alexander v. South Carolina State Conference of the NAACP 2023.

Alexander et al. v. NAACP 2023.

References

Abbott v. Perez, 585 U.S. ___ (2018).

Alexander v. South Carolina State Conference of the NAACP, 602 U.S. ___ (2024).

Beaumont, Thomas. 2016. “AP Fact Check: Trump’s Bogus Birtherism Claim Against Clinton.” Associated Press, September 21, 2016.

Berzon, Alexandra, and Nick Corasaniti. 2024. “Trump’s Allies Ramp Up Campaign Targeting Voter Rolls.” New York Times, March 3, 2024.

Blackmon, Douglas A. 2009. Slavery by Another Name: The Re-Enslavement of Black Americans from the Civil War to World War II. New York, NY: Anchor Books.

Blair, Hunter, David Cooper, Julia Wolfe, and Jaimie Worker. 2020. Preempting Progress. Economic Policy Institute, September 2020.

Boustan, Leah Platt. 2017. Competition in the Promised Land: Black Migrants in Northern Cities and Labor Markets. Princeton, NJ: Princeton Univ. Press.

Brennan Center for Justice. 2023 Voting Rights Restoration Efforts in Florida. August 2023.

Brennan Center for Justice. n.d. “Disenfranchisement Laws” (web page). Accessed August 26, 2024.

Brief of Amici Curiae Historians in Support of Appellees and Affirmance, Alexander v. South Carolina State Conference of the NAACP, 602 U.S. ___ (2024) (No. 22-807) 2023.

Cardon, Nathan. 2017. “‘Less Than Mayhem’: Louisiana’s Convict Lease, 1865-1901.” Louisiana History: The Journal of the Louisiana Historical Association 58, no. 4: 417–441.

Chen, M. Keith, Kareem Haggag, Devin G. Pope, and Ryne Rohla. 2022. “Racial Disparities in Voting Wait Times: Evidence from Smartphone Data.” The Review of Economics and Statistics 104, no. 6: 1341–1350. https://doi.org/10.1162/rest_a_01012.

Childers, Chandra, Dave Kamper, and Jennifer Sherer. 2024. “Operation Dixie Failed 78 Years Ago. Are Today’s Southern Workers about to Change All That?” Working Economics Blog (Economic Policy Institute), May 14, 2024.

Childers, Chandra. 2023. Rooted in Racism and Economic Exploitation: The Failed Southern Economic Development Model. Economic Policy Institute, October 2023.

Childers, Chandra. 2024a. Breaking Down the South’s Economic Underperformance. Economic Policy Institute, June 2024.

Childers, Chandra. 2024b. The Evolution of the Southern Economic Development Strategy. Economic Policy Institute, May 2024.

Clark, Alexis. 2024a. “How Southern Landowners Tried to Restrict the Great Migration.” History, January 3, 2024.

Clark, Doug Bock. 2024b. “Election Deniers Secretly Pushed Rule That Would Make It Easier to Delay Certification of Georgia’s Election Results.” ProPublica, August 18, 2024.

Coleman, Kevin J. 2015. The Voting Rights Act of 1965: Background and Overview. Congressional Research Service, July 2015.

Darling, Marsha J. Tyson. 2024. “A Right Deferred: African American Voter Suppression after Reconstruction.” Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, July 3, 2024.

Democracy Now. 2022. “Native Americans Helped Democrats Carry Arizona in 2020. Now Their Voting Rights Are Under Attack.” YouTube video. Published November 8, 2022.

Desmond, Matthew. 2019. “American Capitalism Is Brutal. You Can Trace That to the Plantation.” New York Times, August 14, 2019.

Dirkson, Menika. 2024. “Convict Leasing in the Family.” African American Intellectual History Society, January 17, 2024.

Domonoske, Camila. 2017. “Trump Adviser Repeats Baseless Claims of Voter Fraud In New Hampshire.” NPR, February 12, 2017.

Dred Scott v. Sandford, 60 U.S. 393 (1856).

Du Bois, W.E.B. 1935. Black Reconstruction in America 1860–1880. New York, NY: Harcourt, Brace.

Economic Policy Institute (EPI). 2021. Unions Help Reduce Disparities and Strengthen Our Democracy (fact sheet). April 23, 2021.

Economic Policy Institute, “Rooted in Racism and Economic Exploitation” (web page). Last updated September 2024.

Economic Policy Institute (EPI). 2024. “Workers’ Rights Preemption in the U.S.” (web page). Last updated June 2024.

Engstrom, Erik J. 2013. Partisan Gerrymandering and the Construction of American Democracy. Ann Arbor, MI: Univ. of Michigan.

Equal Justice Initiative (EJI). 2018. Segregation in America. 2018.

Equal Justice Initiative (EJI). 2020. Reconstruction in America: Racial Violence After the Civil War, 1865–1876. Accessed, August 26, 2024.

Equal Justice Initiative (EJI). n.d.a. “On This Day, Apr 24, 1877: Hayes Withdraws Federal Troops from South, Ending Reconstruction” (web page). Accessed August 26, 2024.

Equal Justice Initiative (EJI). n.d.b. “On This Day, May 12, 1898: Louisiana Officially Disenfranchises Black Voters and Jurors” (web page).

Equal Justice Initiative (EJI). n.d.c. “On This Day, Nov 09, 1866: Texas Legislature Authorizes Leasing of County Jail Inmates for Profit” (web page). Accessed September 11, 2024.

Equal Justice Initiative (EJI). n.d.d. “On This Day, Nov 22, 1865: Mississippi Authorizes ‘Sale’ of Black Orphans to White ‘Masters or Mistresses’” (web page). Accessed August 26, 2024.

Foner, Eric. 1993. Freedom’s Lawmakers: A Directory of Black Officeholders During Reconstruction. Oxford, UK: Oxford Univ. Press.

Fowler, Stephen. 2021. “Georgia Governor Signs Election Overhaul, Including Changes to Absentee Voting.” NPR, March 25, 2021.

Franklin, John Hope. 1994. Reconstruction After the Civil War: Second Edition. Chicago, IL: Univ. of Chicago Press.

Frey, William H. 2022. A ‘New Great Migration’ Is Bringing Black Americans Back to the South. Brookings Institution, September 2022.

Gibson, Campbell, and Kay Jung. 2002. “Historical Census Statistics on Population Totals by Race, 1790 to 1990, and by Hispanic Origin, 1970 to 1990, for the United States, Regions, Divisions, and States.” U.S. Census Bureau Working Paper no. POP-WP056, September 2002.

Gordon-Reed, Annette. 2011. Andrew Johnson: The American Presidents Series: The 17th President, 1865–1869. New York, NY: Times Books

Hannah, John A., Eugene Patterson, Frankie Muse Freeman, Erwin N. Griswold, Theodore M. Hesburgh, Robert S. Rankin, and William L. Taylor. 1965. Voting in Mississippi. United States Commission on Civil Rights, 1965.

Hulse, Carl. 2022. “After a Day of Debate, the Voting Rights Bill Is Blocked in the Senate.” New York Times, January 19, 2022.

Kelley, Erin. 2017. “Racism & Felony Disenfranchisement: An Intertwined History.” Brennan Center for Justice, May 2017.

University of Maryland (UMD), Hornbake Library. 2016 “Martin Luther King, Jr.’s Speech to AFL-CIO.” Special Collections & University Archives (blog). January 18, 2016.

Leadership Conference Education Fund (LCEF). 2019. Democracy Diverted: Polling Place Closures and the Right to Vote. September 2019.

Levine, Sam. 2024. “Georgia Election Deniers Helped Pass New Voting Rules. Many Worry It’ll Lead to Chaos in November.” Guardian, August 23, 2024.

Lewis, John, and Archie E Allen. 1972. “Black Voter Registration Efforts in the South.” Notre Dame Law Review 48, no. 1: 105–132.

Li, Michael. 2023. Alabama’s Congressional Map Struck Down As Discriminatory—Again. Brennan Center for Justice, September 7, 2023.

Li, Michael. 2024. Preclearance Under the Voting Rights Act (explainer). Brennan Center for Justice. March 11, 2024.

Litwack, Leon F. 1965. North of Slavery: The Negro in the Free States. Chicago, IL: Univ. of Chicago Press.

Maye, Adewale A. 2022. “The Freedom to Vote Act Would Boost Voter Participation and Fulfill the Goals of the March on Selma.” Working Economics Blog, (Economic Policy Institute), January 13, 2022.

McCarthy, Justin. 2020. “Confidence in Accuracy of U.S. Election Matches Record Low.” Gallup, October 8, 2020.

Mississippi Civil Rights Museum (MCRM). 2024. “Mississippi in Black & White, 1865–1941” (web page). Accessed July 3, 2024.

Mississippi Department of Archives and History (MDAH). 2024. “The Mississippi Constitution of 1890 as originally adopted” (web page). Accessed August 29, 2024.

Mower, Lawrence. 2022. “Police Cameras Show Confusion, Anger over DeSantis’ Voter Fraud Arrests.” Tampa Bay Times, October 18, 2022.

National Urban League (NUL), Department of Research and Investigations. 1930. Negro Membership in American Labor Unions. January 1930.

Office of the Governor of the State of Alabama (OGSAL). 2024. “Governor Ivey & Other Southern Governors Issue Joint Statement in Opposition to United Auto Workers (UAW)’s Unionization Campaign” (joint statement). April 16, 2024.

Patterson-Payne, Jasmine, and Adewale Maye. 2023. A History of the Federal Minimum Wage: 85 Years Later, the Minimum Wage Is Far from Equitable. Economic Policy Institute, August 2023.

PBS. n.d.a “Southern Violence During Reconstruction” (web page). Accessed August 26, 2024.

PBS. n.d.b. “Murder in Mississippi” (web page). August 26, 2024.

Porter, Nicole D., Alison Parker, Trey Walk, Jonathan Topaz, Jennifer Turner, Casey Smith, Makayla LaRonde-King, Sabrina Pearce, and Julie Ebenstein. 2024. Out of Step: U.S. Policy on Voting Rights in Global Perspective. The Sentencing Project, June 2024.

Rucho v. Common Cause, 588 U.S. ___ (2019)

Rudensky, Yurij, Ethan Herenstein, Peter Miller, Gabriella Limón, and Annie Lo. 2021. Representation for Some. Brennan Center for Justice, July 2021.

Russ, William A. 1934. “Registration and Disfranchisement Under Radical Reconstruction.” The Mississippi Valley Historical Review 21, no. 2: 163–180. https://doi.org/10.2307/1896889.

Samuel, Terence. 2016. “The Racist Backlash Obama Has Faced During His Presidency.” Washington Post, April 22, 2016.

S. Exec. Doc. No. 40-53 (2. Sess. 1868).

Shafer, Ronald G. 2021. “The ‘Mississippi Plan’ to Keep Blacks from Voting in 1890: ‘We Came Here to Exclude the Negro.’” Washington Post, May 1, 2021.

Singh, Jasleen, and Sara Carter. 2023. States Have Added Nearly 100 Restrictive Laws Since SCOTUS Gutted Voting Rights. Brennan Center for Justice, June 2023.

Thornton, William. 2024. “Kay Ivey Says Alabama’s Economic Model Is ‘Under Attack’ with Auto Union Push.” AL.com, January 11, 2024.

Torres-Spelliscy, Ciara. 2019. “Everyone Is Talking about 1619. But That’s Not Actually When Slavery in America Started.” Washington Post, August 23, 2019.

Trump, Donald J. 2020. “Tens of Thousands of Votes Were Illegally Received after 8 P.M. on Tuesday, Election Day, Totally and Easily Changing the Results in Pennsylvania and Certain Other Razor Thin States. As a Separate Matter, Hundreds of Thousands of Votes Were Illegally Not Allowed to Be OBSERVED…” Twitter, @realDonaldTrump, November 7, 2020, 8:20 a.m.

U.S. Census Bureau. 1870. “Table I. Population of the United States—By States and Territories, in the Aggregate, and As White, Colored, Free Colored, Slave, Chinese, and Indian, at Each Census” [Pdf file], published 1870.

U.S. Census Bureau. 2024. “Table A-9. Historical Reported Voting Rates: Reported Voting Rates of Total Voting-Age Population in Presidential Election Years, by Selected Characteristics: November 1964 to 2020” [Excel file], published May 30, 2024.

U.S. Commission on Civil Rights (USCCR). 1968. Political Participation. May 1968.

U.S. Commission on Civil Rights (USCCR). 2018. Assessment of Minority Voting Rights Access In the United States. 2018.

U.S. Federal Register (USFR). 2024. Estimates of Voting-Age Population for 2023, 89 Fed. Reg. 22118–22119 (March 29, 2024).

U.S. Library of Congress (LOC). 1876. Radical members of the first legislature after the war, South Carolina. South Carolina, ca. 1876. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/97504690/

U.S. Library of Congress (LOC). 1882. The Congressional Districts of South Carolina as “Gerrymandered” by the Democracy in 1882. Map. https://www.loc.gov/item/2015588077/

Uggen, Chris, Ryan Larson, Sarah Shannon, and Arleth Pulido-Nava. 2020. Locked Out 2020: Estimates of People Denied Voting Rights Due to a Felony Conviction. The Sentencing Project, October 2020.

United States Congress, Senate (USCS). 1865. Message of the President of the United States. Washington, DC, 1865. Pdf. https://www.loc.gov/item/2022699613/

Ura, Alexa. 2021. “The Hard-Fought Texas Voting Bill Is Poised to Become Law. Here’s What It Does.” Texas Tribune, August 30, 2021.

Vasilogambros, Matt. 2024. “New Voter Registration Rules Threaten Hefty Fines, Criminal Penalties for Groups.” Stateline, June 7, 2024.

Waxman, Olivia B. 2022. “The Legacy of the Reconstruction Era’s Black Political Leaders.” Time, February 7, 2022.

Widra, Emily. 2024. States of Incarceration: The Global Context 2024. Prison Policy Initiative, June 2024.

Williams, Jhacova. 2020. “This MLK Day, Remember Emmett Till and Voter Suppression.” Working Economics Blog (Economic Policy Institute), January 16, 2020.

Wills, Matthew. 2019. “Racial Violence as Impetus for the Great Migration.” JSTOR Daily, February 6, 2019.