Sottotitolo:

In several European countries growing populist movements are threatening the representative democracy and the entire post-war social democratic settlement.

Abstract:

In several European countries growing populist movements are threatening the representative democracy and the entire post-war social democratic settlement. Voters are faced with: the global economic crisis, and the associated mass unemployment; enhanced international competition and protectionist temptations; rampant inequalities and the challenge of migrations, concentrated in a few areas and sectors; the euro crisis and the prospect of all having to share the cost of bailing out countries perceived as non-deserving; the exploitation and resulting demise of the welfare state. In short, they have strong objections both to re-distribution and to lack of re-distribution of income and wealth, i.e. ultimately to the re-distribution processes such as they are. In these conditions, voters will abandon nebulously felt democratic powers in return for equally nebulously-offered protection of their living standards and their way of life.

The spectre haunting Europe in the spring of 2011 is Populism. The search for political support, from votes in democratic elections to acceptance of policies between elections, through appealing to the self-interest of large and vocal groups by unscrupulous, even immoral means, has become a mainspring of political activity. Such means consist mostly of promises that are either: 1) impossible to deliver, or 2) temporarily feasible but non-sustainable on the proposed scale in the longer run, or 3) feasible and sustainable only at the very heavy cost of compromising an overriding public interest, including the rule of law. An example of the first is a manifesto commitment to stopping immigration altogether (by border controls or building walls), or making it illegal and repatriating immigrants; the second, an overambitious programme of large-scale public works, or a commitment to overgenerous welfare provisions and inter-regional transfers; the third encompasses criminality in government activities such as condoning and encouraging illegal buildings or tax evasion. It follows that, of necessity, a populist leader must be an inveterate and shameless liar, sometimes a rigid ideologue, often a criminal.

Paradoxically it is the nature of liberal democracy that generates populist politicians. The requirement to submit to the vote at regular, relatively short intervals makes for the need to try and fool all of the people at least some of the democratically critical time; or fool a majority of supporters for some of the time, until it becomes absolutely obvious to that majority that you cannot deliver at all, or can only do it for a short time, or that the costs of keeping promises are immense and make everybody worse-off. And when the opposition to populism is divided or gormless, populism can thrive even without commanding a majority.

In a representative democracy the purchase of the people’s representatives directly, and very cheaply with respect to the value of what you can obtain in exchange, including immunity from prosecution and blanket impunity, can be even cheaper than taking over a derelict but branded party or founding your own afresh (though this can also be a very profitable business). And once you have built temporary power, you do not even have to buy the people’s representatives out of your own pocket, for you can reward them at public expense. These long-standing techniques are greatly facilitated by the modern possibilities of building up monopolistic or quasi-monopolistic control of the media, in the absence of legislation against the conflicts of interest that are bound to arise.

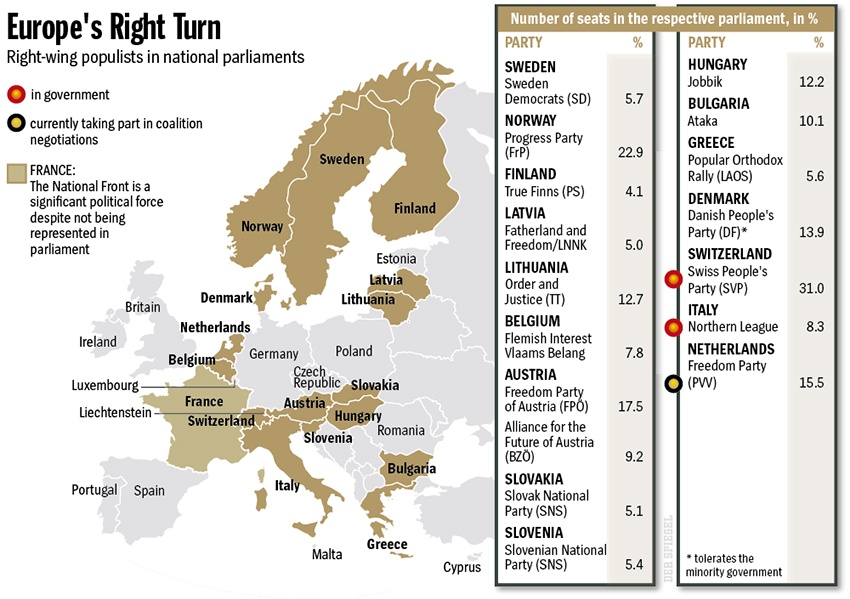

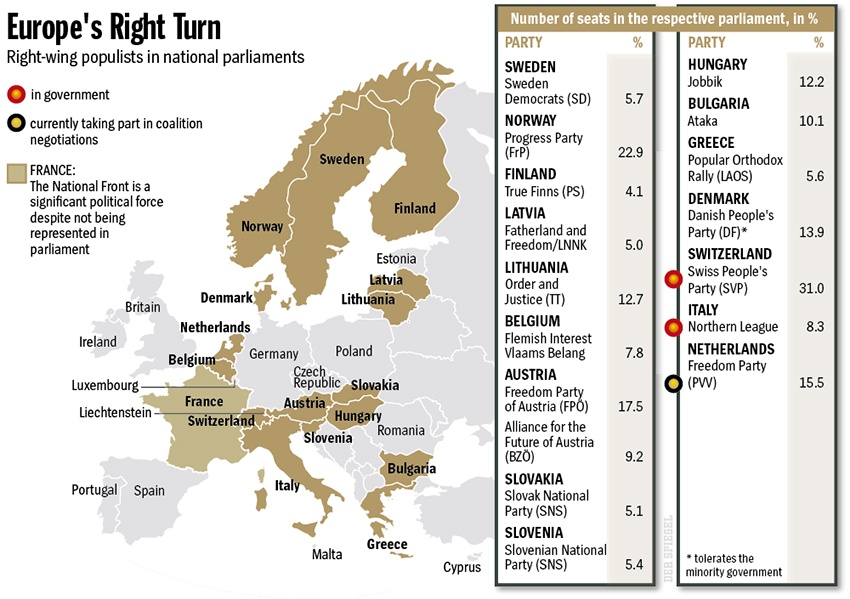

United States pork barrel politics currently displays its populist public face in the Tea Party but while the Obama government is in power populism is held under some restraint. In Europe we already have the real thing. Clearly Italy with its inordinately disreputable and discredited Premier on trial for a remarkably broad array of criminal activities, backed by his populist ally and accomplice the Northern League, ideologically committed to undeliverable economic, fiscal and cultural policies (yet making fast progress beyond its current 8.3% of the seats), is what I had in mind in characterizing populism. But European populism, or populist-like policies, is widespread and gaining support elsewhere. The map reproduced below is from Spiegel on line (15 April 2011), just before the Finnish elections, therefore putting True Finns at only 4% of the seats. Spiegel – quite rightly in the circumstances – uses indifferently “right wing”, “right wing populist” and “populist” tout court.

In Finland, on 17 April half a million voters (19%) endorsed the racist, xenophobic and eurosceptic, anti-abortion “True Finns” party, catapulting it into third position, neck and neck with the first two parties. Its leader Timo Soini holds the balance of power in the formation of a new government. There may be dangerous repercussions on the measures to rescue the Euro agreed by the European Council on 24-25 March, including the additional billions for the euro bailout fund, the planned reform of the fund, and the rescue package for Portugal which is still to be finalized. True Finns are opposed to assisting "wasteful countries" (like Greece, Ireland and Portugal). "We were too soft on Europe," says Soini; Finland should not be made to "pay for the mistakes of others."

Recently right-wing populist parties have impacted government formation in Belgium, the Netherlands and, more recently, in Sweden. The SD (Sweridge Democraterna) cleared the minimum 4% threshold to enter the Riksdag where it obtained 5.7% of the seats, enough to deprive the incumbent center-right coalition of an absolute majority. Last year the anti-Islam anti-EU Dutch Freedom Party gained third position with 15.5% of the seats, making Premier Mark Rutte dependent on the goodwill of its populist leader Geert Wilders. In Belgium the Flemish Interest/Vlaams Belang obtained 7.8% of the seats. In Norway the so-called Progress Party holds 22.9% of the seats. In Denmark the anti-immigration, anti-Islamic Danish People's Party, that supported a center-right minority government for almost ten years, is now the third party in Parliament with 13.9% of the seats. In Switzerland the right-wing People’s Party (PV) is the largest group in the Federal Assembly with 31% of the seats. In Austria the Freedom Party (FPO), founded by Jorg Haider, and the Alliance for the Future of Austria hold 17.5% and 9.2% of the seats respectively. In Romania in the European elections of 2009 the Great Romania Party obtained 8.7% of the votes. Populist representation in Parliament is also present in Latvia (Fatherland and Freedom LNNK 5%), Lithuania (Order and Justice IT 12.7%), Slovakia (Slovak National Party, 5.4%), Bulgaria (Ataka 10.1%), Greece (Popular Orthodox Rally LAOS 5.6%). In France, the Front National of Marine Le Pen is not represented in Parliament but gained 15% of the vote in the first round of administrative elections, and 12% in the second round; the latest opinion polls give her the top position in the first round of the forthcoming presidential elections. The only other country in continental Europe without populist representation in Parliament is Germany.

These are depressing results for any progressive of left or right but insofar as they are expressions of voter-support for divergent, non-progressive policies, are still within the aegis of representative democracy; unlike what is happening in Italy, where the state itself is under assault from criminal and sectional interests, and is classically undefended by a fragmented and incompetent opposition.

It is Hungary, however, that can be defined as a laboratory for the new, national, populist Europe, with mounting aspirations to ethnic identity and zero tolerance of social diversity, with the Hungarian national-conservative Fidesz party rising to power last year behind populist calls for law, order and more police. (Soon after he was sworn in, Prime Minister Viktor Orbán promised a "noticeable increase in public security within two weeks.") Furthermore, “The ruling Fidesz party of Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán used its two-thirds majority to whip a new constitution through parliament on Monday [18 April 2011], and critics across Europe are in uproar. The move, they fear, will convert the party's conservative, nationalist ideology into a state doctrine, cement its power well beyond the end of its term and upset the democratic system of checks and balances” (Spiegel online, 19 April). The new Constitution reduces the powers of the constitutional court and broadens government powers over the magistrature, over budgetary and fiscal matters and over the media – extending it, through government nominees, beyond the current government tenure that is expected to end in 2014. The new authority controlling the media since the beginning of the year, Nmhh, already exercises censorship with orwellian efficiency. This is the very essence of Berlusconi’s project.

On the night the new Hungarian constitution was approved the German public TV network ARD commented: “The constitutional state has largely been abolished, future elections are effectively meaningless, the media are being whipped into line, as are theaters and museums and everything else that could shape the nation's culture." … "Barely a trace remains of pluralism, of variety, of the basic features of a free society. If you talk to people in Hungary about politics these days, you're confronted with fear, like in the days of East Germany. In this state, Hungary no longer belongs in the EU. It is a disgrace for Europe. But Europe is saying nothing."

The Süddeutsche Zeitung commented: "The constitution enshrines a spirit of ideological, ethnic intolerance, both externally and domestically. Some are being reminded of the fascist rhetoric in Europe between the world wars. Neighboring countries are getting unpleasant memories of the cultural arrogance and power of the Hungary of old, whose Magyarization programs they were subjected to. The new constitution claims that the state of Hungary represents all other Magyars, meaning the three million living in neighboring countries." (the quotes from both sources are taken from Spiegel online, 19 April).

In the 2010 Hungarian elections the extreme right party Jobbik also entered Parliament with 16.7% of the vote. In 2009 the Jobbik-backed para-military Hungarian Guard was banned, but new private militias have been re-created and have been harassing Roma villages over Easter, forcing the Roma population to evacuate, and have been involved in beatings and clashes (Spiegel online, 28 April; see also their Photo Gallery). “The police and the judiciary have lost control over the growing right-extremist citizen groups and paramilitary-style gangs. In recent months, extremists have repeatedly staged marches, primarily in eastern Hungary, against "Gypsy criminality." And police in the villages which have been targeted have shown a preference for standing aside.” The Hungarian state appears to have retreated from certain regions and left them to the right-wing vigilantes. So much for the promise of a noticeable increase in public security.

In Hungary the populist Executive has succeeded in identifying itself and its values with the state and has permanently altered what was a representative democracy, and by which it came to power, so that its populist policies cannot be removed by democratic vote. It is here, in the embodiment of populist values in place of democratic values within the modern state, rather than as policies on offer to the electorate in party manifestos, that the threat to the entire post-war social democratic settlement lies.

Voters are faced with: the global economic crisis, and the associated mass unemployment; enhanced international competition and protectionist temptations; rampant inequalities and the challenge of migrations, concentrated in a few areas and sectors; the euro crisis and the prospect of all having to share the cost of bailing out countries perceived as non-deserving; the exploitation and resulting demise of the welfare state. In short, they have strong objections both to re-distribution and to lack of re-distribution of income and wealth, i.e. ultimately to the re-distribution processes such as they are. In these conditions, voters will abandon nebulously felt democratic powers in return for equally nebulously-offered protection of their living standards and their way of life.

There is, too, a knock-on effect in other EU countries, including those up to now relatively unaffected by populism (whether as a result of their voting system or the maturity of their democratic values) but vulnerable to the wave of North African refugees connected with participation in the Libya mission, causing bickering and conflict, and leading to a waning of solidarity among these countries in their determination to rid Europe of a rogue state on its Mediterranean borders.

What can we do? Re-value political participation and activism. Never accept that "politics is dirty" or that "all politicians are corrupt", this is false. Fight indifference in all its forms. Forge political alliances by looking for common ground rather than indulging in unaffordable splits and unacceptable assaults upon people’s aspirations and self-sufficiency. Avoid dogmatism. Defend the democratic state and the rule of law. Speak up; those with access to media or academic outlets should use it to argue for representative democracy and refute the frightened selfishness of populist policies. And be counted. Never fail to vote whenever you have the opportunity