Sottotitolo:

May Greece and Ireland succeed in stabilizing the growth of public debt? To maintain a primary surplus of ten or more points for several years is a classical “mission impossible”. The only alternative is the issue of euro-bonds, but...

What happens when the governments are shortsighted like the mean citizen? This is what we will verify in the next period, may be one year or even less. Public opinion in continental Europe thinks that Greece (with all the other Mediterranean countries) and Ireland deserve what is happening. Why should we pay for their faults? Or better for their sins? That’s the mantra played in Germany by both conservative TV and newspapers.

But to understand the German reaction to the Junker-Tremonti proposal of euro-bonds we need to look beyond the simple-minded reactions; the point is that in the Maastricht Treaty the only threat to the economic stability could come from public budget deficits of a country, where politicians try to take advantage from the participation to the common currency. For this reason in the Treaty there is the “no bail-out clause” and a Stability Pact was added to the excess deficits’ articles; first of all, of course, the ECB is absolutely independent from the political Institutions. For the same reason there was no need of having an European Fund able to deal with a situation of liquidity or insolvency crisis, a Fund which could consolidate and restructure the debt.

What happened instead is that the crisis stemmed from the private financial system, and that caused recession and spreading of public deficits, necessary also in order to save the banks. It is true that in the Greece Papandreou’s government revealed that the previous government had concealed the level of public deficit through creative accounting (with the support of private international banks), behavior which, by the way, was not illegal according Bruxelles rules. But there are reasonable reasons to think that, without the financial crisis, the Greek government would have been able to deal with the public deficit.

The Irish crisis is a good example on how a debt is origined, which, passing from the banks to the public finance, changes only the subject that is insolvent. In 2007 Irish public debt (as a ratio of GDP) was only 25% and the glory of the Celtic tiger was celebrated everywhere. Now the reason why Angela Merkel (with Sarkozy) opposes to the euro-bonds proposal is that in this way “pigs” countries would loose the necessary determination to cut public expenditures (and if necessary increase taxes), liberalize the labour market and the economy in general. This is exactly was Papandreou’s government is doing in Greece, but what could do Ireland, given the low public expenditure and absolutely free labour market? Still the Irish government is cutting public expenditure and rising personal taxes (but not the corporate one).May Greece and Ireland succeed in stabilizing the growth of public debt? There are very few chances. Their governments should deal with a strong differential of the cost of debt and the rate of growth of GDP; suppose that a cut of one point of public deficit lowers the growth of GDP of half a point

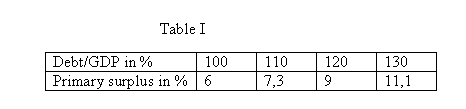

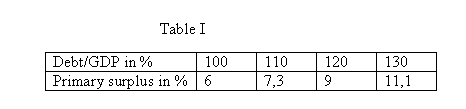

In this case a differential of three percentage GDP points between the cost of debt and the rate of growth at different levels of debt/GDP ratio implies a primary surplus as in table I:

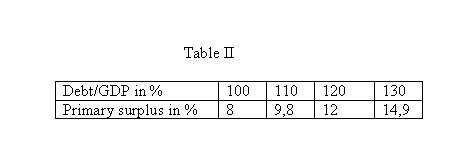

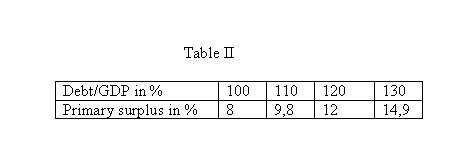

Moreover, if we assume that the differential would be of four percentage GDP points, a primary surplus that will stabilize the debt ratio is shown in table II:

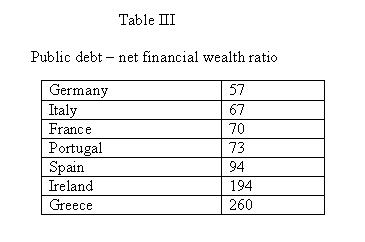

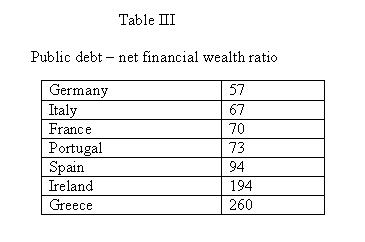

Historical experience in Scandinavian countries and Italy, in the eighties and nineties shows that a country may aiming at obtaining a primary surplus of more that five points for few years, but not for many. To maintain a primary surplus of ten or more points for several years is a classical “mission impossible”. Are there alternatives? The classical one is a ricardian extraordinary tax on wealth; but, looking at table III, the ratio between expected public debt and families financial wealth is near or over two times in Ireland and Greece. This hypothesis is, in theory, open to Italy, Portugal, and even Spain, but very difficult for the two countries under attack.

The other scenario deals with is default; if the Greek of Irish government will realize that the burden of the stabilization is too heavy, a way out could be debt restructuring or declaration of default. This is a realistic option if the country doesn’t need to issue new debt, that is if the budget, after default, is balanced . In this case French and German banks will have big problems, since their credit towards Greece and Ireland are around 300 euro billions. And banks troubles are Government’s trouble.

The issue of euro-bonds was a proposal made in 1993 by Jacques Delors, aiming to obtain a sustainable rate of growth; the proposal has been put forward by several experts like Stuart Holland ( Insight A European Monetary Fund, Recovery and Cohesion ). More recently Bruegel, a Belgian “think-tank” presented a proposal for an European mechanism to sovereign debt crisis resolution, and similar proposals has been put forward by Mario Monti, in a report to Barroso, and by Vincenzo Visco, former minister of Finance under Prodi government. In these cases the aim is to decrease the cost of public debt. It is a fair guess that these proposals could lower the danger for the European economies as a whole, not only for “pigs” countries. Would Merkel and Sarkozy be less shortsighted they will realize that risk, for their own countries, is greater with the continuous denial of a European mechanisms for stability and growth.