Sottotitolo:

Paper presented at the 16th ILERA World Congress Philadelphia/USA, 2 - 5 July, 2012

1 The issue

Various forms of atypical (non-regular or non-standard) employment are neither a new phenomenon nor limited to individual countries. The concrete forms differ significantly from country to country but their overall increase over the last two or three decades constitutes a general trend (Houseman/Osawa 2003; JILPT 2011). Therefore, they cannot be neglected in public policy and research on changes of the employment systems.

This paper deals with developments, present extent and patterns and, thus, provides an encompassing, so far missing updated overview for Germany. Its first part presents definitions and delimitations. It differentiates explicitly between normal (or standard) employment (Normalarbeitsverhältnis) and various atypical forms; furthermore, it introduces the crucial distinction between atypical and precarious employment on the basis of explicitly indicated social criteria. The second part describes the development and structures; in order to be able to analyze long-term consequences. It covers the period since German reunification in 1990, an important break also for labor market. The third part presents theoretical explanations that are widely missing in existing research.

2 Definitions and delimitations

2.1 Standard employment and forms of atypical employment

Atypical employment is usually defined in purely negative terms in contrast to the so-called standard employment (Mückenberger 1985 and 2007). It constitutes a statistical, summarizing mixture and includes rather heterogeneous substantive forms that need to be explicitly distinguished in empirical analysis. The frequently used point of departure is standard employment characterised by the following features:

- Full-time employment with an income sufficient to enable independent subsistence,

- permanent employment contract,

- complete integration into the social security systems (particularly unemployment, health and pension insurance),

- work relationship and employment relationship are identical,

- employees are subject to the direction by the employer.

In correspondence with other comparative research on our issues (Kalleberg 2000, Vosko 2010) we use this term as a nominal definition and exclusively in an analytical, not in a normative sense. The procedural reason is that we need an unequivocal point of departure and reference. The substantive reason is that social security systems in major continental western European countries, especially in Germany as a conservative welfare state (Esping-Andersen 1990), strictly refer to these criteria (so-called principle of equivalence): Individual entitlements are closely interrelated with these preconditions.

Atypical forms deviate from standard employment in terms of at least one of the indicated criteria:

- Part-time employment (Teilzeitarbeit), the traditional form, is characterized by less regular weekly working hours than collective agreements define for standard employment (about 35 to 40 hours); pay is proportionally reduced.

- Marginal employment (geringfügige Beschäftigung) represents a specific German version of part-time employment that was extended in 2003/2004 by the so-called Hartz laws. Monthly earnings resulting from these so-called “mini-jobs” have to remain below the threshold of 400 €.

- The Hartz laws also introduced so-called “midi-jobs”, another German peculiarity, whose monthly remuneration limits are between 401 and 800 €.

- Fixed-term (or temporary) employment (befristete Beschäftigung) means that the contract ends automatically after an indicated period; existing legal provisions of dismissal protection do not apply. There are two sub-forms: There is either no necessity to indicate specific reasons for the termination or various reasons are acceptable (among others, maternal leave).

- Agency work (Leih- or Zeitarbeit), or temporary help agency, as it is called in other national contexts (Osterman/Burton 2005), differs from all other forms because of its tripartite relationship between the employee, the agency and the company hiring the employee. This peculiarity causes the important triangular link between the employment relationship (between the agency and the employee) and the work relationship (between the company as a client and the employee). If companies make use of his form they have to pay the agency an extra premium on top of the (comparatively low) wage employees are paid.

- Overviews disagree whether self employment (Selbstständigkeit) should be considered as a form of atypical employment. We integrate this form into our analysis because of its long-term consequences for social security systems (for similar approaches, Houseman/Osawa 2003, Vosko 2010). We focus on the sub-group with no other employees, the so-called solo-self-employment.

The lines of demarcation between these forms are not always clear-cut. First of all, individual forms can be combined, among others agency or part-time employees can at the same time have a fixed-term contract. Furthermore, the distinction between full-time and part-time employment depends on the selected threshold of weekly hours. The number and proportion of atypical employees obviously varies according to these definitions.

2.2 Risks of precariousness

The more recent boom in atypical employment leads obviously to an increase in various social risks. Therefore, the relationship between atypical and precarious employment has to be clarified (Rodgers/Rodgers 1989). In political discussion and academic discourse, both terms are often used as synonyms (for others Dörre 2006, Standing 2011). However, this popular approach remains indeterminate and unfocused for various reasons: It does not differentiate between various dimensions of precariousness to be indicated below, fails to take various contextual factors (as individual vs. family income) into consideration, and does not allow distinguishing between existing degrees of precariousness.

We introduce four objective, quantifiable dimensions of precariousness that have to be considered jointly. First of all, these generated risks are of short-term nature, i.e. they occur during employment. However, they are also of long-term nature, i.e. their consequences occur only after the end of working life because social security provisions strictly depend on the former participation in the labor force. It is of utmost importance to take into consideration that these frequently neglected consequences extend far beyond the labor market into the period of retirement (Fuller 2009). In other words, the traditional, rigorous demarcation between institutions of the labor market and social policy is obsolete in the case of atypical forms.

The four dimensions of precariousness are:

- An income at subsistence level is usually defined in comparative analysis (ILO, OECD) as at least two thirds of the median wage.

- Employment stability is defined as the opportunity of continuous employment in contrast to stability of a specific workplace (or job security). The latter is the traditional, the former the present, much broader version of stability.

- Employability means the life-long ability of individuals to find and to maintain employment and even to adjust to structural changes (first of all, by means of further training and additional qualifications). More recently, this concept has played a major role within the European Employment Strategy (COM (2011) 11final).

- Integration into the different systems of social security, above all pension systems but also health and unemployment insurance. Individual entitlements depend on this integration. One should distinguish between entitlements from one’s own employment and entitlements derived from others’ activities.

Numerous empirical surveys show that all forms bear higher risks of precariousness. With regard to the first criterion, wages, all forms of atypical employment are disadvantaged compared to standard employment when individual features are examined. There are differences not only between standard and atypical employment but also between various atypical forms (Brehmer and Seifert 2008). They are particularly crass in the case of marginal employees (Anger and Schmid 2008), less in the case of agency workers (Sczesny et al. 2008), but also fixed-term (Giesecke and Gross 2007) and part-time employees (Wolf 2003) are not on the same level as standard employment. Even if one takes the individual household context into account, this situation creates problems for subsistence as well as risks of poverty during and after working life. Already almost 4 per cent of all employees receive public benefit payments because of their low income (Möller et al. 2009). The majority of employees in the low-wage sector that is characterized by high growth rates throughout the 2000s have mini-jobs.

There are also significant differences in employment stability. Particularly agency work (Brenke 2008, Kvasnicka 2008) and fixed-term employment (Bookmann/Hagen 2006, Giesecke/Gross 2007) are unstable compared with standard employment.

Atypical employees are also disadvantaged in access to company based further training (Baltes/Hense 2006, Reinkowski/Sauermann 2008). The opportunity for improving one‘s own employability on the internal as well as external labor market is limited because risks of precariousness can be cumulative and atypical employees do not have the necessary financial resources to compensate for discrimination in access to continuous vocational training by taking the initiative of their own. There is a danger of falling into a sort of vicious circle consisting of repeated periods of atypical employment punctuated by phases of unemployment that is difficult to break out of and brings considerable long-term social risks for the individual concerned.

The importance of the described risks of precariousness could be regarded less serious if forms of atypical employment mainly served as a stepping stone to the labor market and constituted a short-term transition to standard employment. However, upward mobility is extremely limited. When fixed-term and agency workers lose their jobs and do not remain unemployed they return to similarly precarious forms of employment (Gensicke et al. 2011)

To sum up, the risks of precariousness are considerably higher for all atypical forms than for standard employment - even though the latter is also not free of precariousness risks (among others, income). However, they also lead to the conclusion that not all forms of atypical employment have to be classified as precarious.

What is relevant in the long term is the insufficient integration of such individuals into the pension insurance system. The low levels of contributions made as a result of long periods of part-time employment or an entire working career spent on mini-jobs – but also unemployment after the expiration of fixed-term jobs – results in individuals only having a claim to pension benefits that are inadequate for subsistence. The changes that have occurred in types of employment increase the risk of old age poverty for the individuals concerned. For years, this issue was regarded as having been solved in Germany, but it could re-emerge in the future unless appropriate measures are taken.

3 Development and structure

3.1 Development and extent

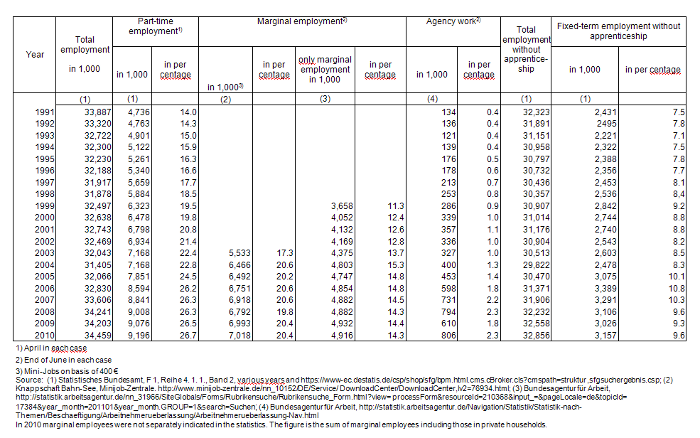

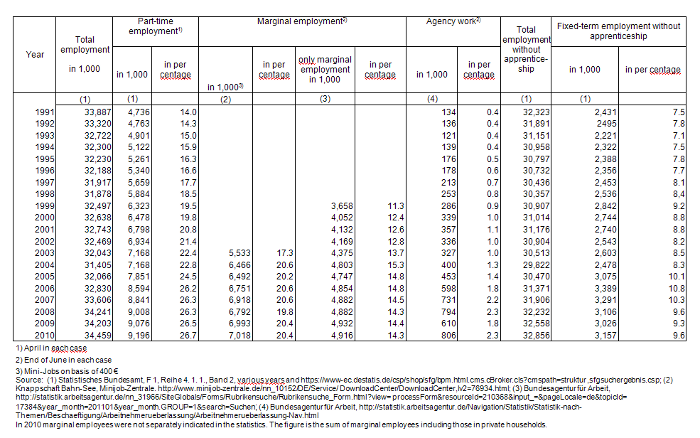

Since the early 1990s all forms of atypical employment have been on the increase, albeit at differing rates and departing from different levels of origin (see table 1).

Table 1: Different forms of atypical employment

- Part-time employment is the most widespread form (more than 26 per cent of all employees), even above EU average. Its long-term, more or less steady increase, independent of the stage of the business cycle, is closely related to the growing participation of women in the labor force. Women still account for more than 80 per cent of all part-time employees because of family reasons – the well known gender gap persists and even exceeds the EU average (Brenke 2011). In addition to those opting voluntarily for part-time, there are also individuals who would prefer to work longer hours if they were offered appropriate jobs; about 20 per cent are involuntary part-timers (destatis 2011). Thus, there is a certain mismatch between preferences on both sides.

- More than 20 per cent of all employees, second only to part-timers, fall into the “mini job” category. After the amendments of the Hartz laws there was initially a marked increase (from 17 to about 20 per cent), later on it more or less stabilised at a high-level. Within this form an explicit distinction has to be made as far as integration into social security systems is concerned: A mini-job can be the only job or a job in addition to non-marginal employment. The former version predominates and accounts for almost 70 per cent of all mini-jobs. This part is in terms of social policy regulation definitely more problematic. About one third would prefer longer working hours if there were offers (Brenke 2011).

- The importance of the new form of midi-jobs is (at about 3.7 per cent of all employees) relatively small in comparison with mini-jobs but higher than agency work. More than one third work full-time, these long working hours indicate low hourly wages because of the existing threshold of 800 €.

- Fixed-term employment has slowly grown to about 10 per cent and, thus, experienced a relatively modest growth compared with other forms. It is quite remarkable that almost one half of all new contracts are fixed-term.

- Agency work continues to account for only a relatively small segment of the labour market and, in purely quantitative terms, constitutes the least important atypical form (of more than 2 per cent of total employment). In comparative perspective its percentage is relatively low. In the long term however, especially since the deregulation of the Hartz laws, it has experienced a large expansion; its unusually high growth rate that led to its duplication throughout the 2000s has triggered a disproportionate level of public interest in this type.

- It is not always possible to distinguish precisely between dependant employment and self-employment (frequently also labelled pseudo self-employment or dependent self employment), as the criteria and lines of demarcation can be rather fluid (Vosko 2010). Most recent empirical analysis indicates that solo-self- employment has increased from almost from 4 to almost 7 per cent of the total workforce. At present this variant is, due to specific labor market instruments, even more frequent than self-employment (Keller/Seifert 2011). In comparative perspective, the overall percentage of self-employment is still low.

If we carefully use the above introduced definitions and exclude overlapping the proportion of atypical forms has increased to more than one third of the workforce. In the early 1990s, the percentage was only about 20 per cent (see table 1). This rapid development means that atypical employment has ceased to constitute merely a marginal segment of the labour market that, therefore, could easily be excluded from any analysis. Normal employment as the (traditional) norm is waning, and atypical forms constitute an increasingly common exception. The expansion of total employment between 2005 and 2008 was largely due to an increase in atypical forms, in particular of mini-jobs and agency work (destatis 2008). The most recent increase since 2010 is to a great extent due to part-time and agency work.

The diversity as well as the composition of the labor force has increased to a considerable degree. In view of this development, the term "pluralization/differentiation of forms of employment” is a more appropriate description of the changes in the employment system than the frequently used reference to a “crisis” or even “erosion” of standard employment (for others Standing 2011). This development does not mean, however, that standard employment will become obsolete. In comparative perspective, Germany does not constitute an exception. Independent of the type of welfare state (especially social democratic, conservative, or liberal) an increase in atypical forms of employment can be observed in all EU member states (above all in the old member states) (Schmidt/Protsch 2009).

3.2 Structural aspects

Employees in these forms of atypical employment differ according to the typical socio-demographic criteria, such as gender, age and level of qualifications as well as sector (Bellmann et al. 2009).

- In most atypical forms women are over-represented to a higher (as in part-time employment) or lower degree (as in fixed-term work). The only exception are agency work because of its distribution across sectors (Puch 20008) and self-employment. In other words, there is a clear gender-specific bias in forms of atypical employment. That also shows findings from comparative analysis (Houseman/Osawa 2003, Vosko et al. 2009). The majority (57 per cent) work in atypical forms, the “new normality” for women, and reinforce the already existing gender-specific segmentation of the labour market. The traditional male breadwinner model of employment has gradually been loosing in importance. The increasing labor force participation of women (at present approx. 75 per cent in Germany) is closely linked to the growth in atypical forms, especially part-time employment and mini-jobs; on the other hand, the share of women in normal employment slightly decreased since the 2000s.

- As far as education levels are concerned there is no unitary distribution. Unskilled individuals hold more frequently atypical jobs than those with completed vocational training or tertiary education. The present form of employment must not correspond with the attained level of education (among others, due to interruptions of employment because of children and longer spells of unemployment). Higher qualifications are more frequent in fixed-term employment and solo-self-employment.

- In terms of age, atypical employment can be found in all groups. But younger employees (15 to 24) with fixed-term employment contracts, who possibly also start on a part-time basis, are clearly over-represented in all forms (with the only exception of part-time employment). The modest increase in the number of fixed-term employees does not indicate a specific age distribution. The likelihood to move to a permanent job increases with the level of education (Hohendanner 2010).

- Non-natives are more frequently employed in atypical forms than Germans. Non-EU foreigners are more frequently affected than citizens of EU member states (destatis 2008).

Furthermore, atypical employment is unevenly distributed across industries. Part-time employment can be found above all in the service sector (42 per cent). Fixed-term contracts are mainly used in industries that are not affected by the business cycle such as health and social services, education and teaching and also public administration (Hohendanner 2010). The sectoral distribution is similar for marginal employment whose main sectors are retail (15 per cent) and hotel and catering (25 per cent) (destatis 2010).

Agency work, by contrast, is largely found in manufacturing though the service sectors have also increased in importance. The majority of employees (71 per cent) are male and work mainly in the metalworking and electrical industry but also as casual employees in other manufacturing industries probably because the Hartz Laws of 2004 removed the ban on limitations of hiring out, the average length of employment has increased.

All in all, these more recent developments strengthen the segmentation of labour markets into core and marginal parts, or “insiders” and “outsiders”.

4 Towards a theoretical explanation

In the existing literature (on Germany as well as other countries) there are lots of empirical studies on atypical employment. They focus on various aspects, such as individual forms and their development, distribution across sectors, socio-demographic data of employees etc. There are, however, next to no theoretical explanations of these more recent phenomena.

This obvious lack of (theoretical) explanations supplementing (empirical) descriptions is surprising for various reasons: In quantitative terms, these forms have gained in importance and constitute at present, as indicated, more than one third of overall employment. Therefore, they cannot be neglected any longer. In qualitative terms, the new microeconomics of the labor market is (implicitly or explicitly) oriented towards the legal framework of regular employment and provides hardly satisfactory explanations for atypical forms. General explanations include globalization, an increase in international competition, structural change, demographic composition and diversity of the labor force as well as the spread of neo-liberalism. These categories are too general and indeterminate; these macro approaches lack a micro foundation.

Transaction cost arguments

The first theoretical attempts try to explain the expansion of atypical forms by means of human capital and transaction costs theories (Nienhüser 2007, Sesselmeier 2007, Neubäumer/Tretter 2008). The first two take the demand side of the labour market as their point of departure and argue that in times of volatile demand atypical forms (above all agency and fixed term work) can reduce labour and redundancy costs and, at the same time, increase flexibility in terms of deployment of human resources whereas the latter one also points to the supply side. The use of atypical forms also enables companies to generate external revenues as, in the case of crisis and declining demand, no core employees have to be dismissed. If these employees, in whose training considerable resources have often been invested, were made redundant, companies would not be able to get any return on their investment and would face also high redundancy payments due to individuals with long tenure. Moreover, there would be no guarantee that these individuals could be reemployed when demand recovers, thus avoiding expensive recruitment and induction costs. On the other hand, one has to take into account transaction costs for induction, information and monitoring of agency workers.

It is further argued on the basis of transaction cost theory that greater division of labor means that induction costs have declined, particularly for unskilled jobs in the service sector, thereby reducing the costs of hiring. In addition, at least in cases where redundancy payments are involved, the costs are lower when employment is shorter. To this extent, it can be advantageous for companies to have, in addition to their core workforce, a second category of employees recruited on a short term, highly flexible basis. This function is of particular importance in the manufacturing industries that depend on great fluctuations of the business cycle. The current crisis illustrates very well how various forms of reduction of working time have enabled companies to maintain their core workforce despite a sharp drop in demand, while at the same time radically reducing their use of agency workers (Herzog-Stein/Seifert 2010). This transaction cost argument is however not able to explain the rising share of marginal employment. In the service sector demand is less volatile and these costs are, therefore, of minor importance. Furthermore, part-time, the most important form in quantitative terms can hardly be explained by transaction cost arguments because it constitutes fairly stable employment conditions.

The development of one, and only one, encompassing explanation seems to be impossible because of the enormous heterogeneity of individual forms whose only common denominator is the fact that they lack at least one central feature of normal employment. In other words, the “one-theory-fits-all-forms” strategy is not very promising.

Our (somehow eclectic) approach adds another layer to an explanation. It makes use of the following ingredients:

- Regulation, or to be more precise deregulation as legal instrument of the state as corporate actor, defines the frame of reference. During the last decades de-regulation has been the most prominent strategy.

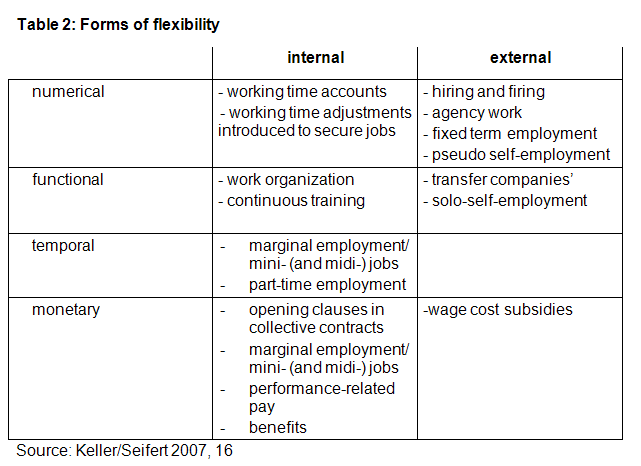

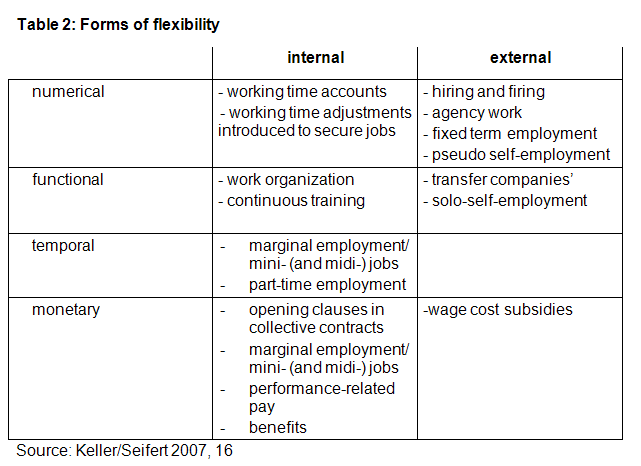

- Atypical forms of employment, whatever their peculiarities, are important or maybe even necessary for the functioning of present labour markets. Nowadays, they constitute strategic means of management and employers because they increase the scope of “flexibility” for enterprises and, to some extent, also for their employees (among others, part-time and in certain cases even mini-jobs). Therefore, existing concepts of flexibility are introduced, broadened and applied to atypical forms of employment.

Deregulation

Over the last two to three decades various measures of deregulation have dominated in next to all countries (Kalleberg 2011) and have extended the scope of flexibility. In Germany the former legal framework was regarded as an important obstacle to cope with the long-lasting unemployment problems. The existing employment protection legislation was considered as an exogenous cost for companies preventing them from adapting to a rapidly changing environment driven by technological change, globalization and fluctuating demand. More recent governments deregulated step by step the legal framework. The most far-reaching reform was undertaken in 2003/04 by the “Gesetze für moderne Dienstleistungen am Arbeitsmarkt” (Laws on Modern Services in the Labor Market, the “Hartz Laws”), which deregulated agency work, fixed-term employment and marginal employment with the aim of promoting the use of atypical employment and thus raising overall employment levels.

The legal framework of atypical employment has been changed as follows:

- Part-time employment (excluding marginal employment): In 2001 the Teilzeit- und Befristungsgesetz (Part-time and Fixed-Term Employment Law) paved the way for an expansion of part-time employment. Employees are entitled to move from full- to part-time but not vice versa. Part-time employment is defined as work with regular weekly working hours less than under regular contractual level and pay reduced accordingly.

- Marginal employment represents a specific variety of part-time employment that is defined in terms of remuneration below a certain level (400 €). The Hartz Laws added two further categories: so-called mini-jobs and midi-jobs. For mini-jobs the previously existing limitation of weekly working time (at a maximum of 15 hours) was abolished. Consolidated contributions to social security systems and taxes amount to 30 per cent and are, in contrast to all other forms, paid exclusively by the employer. These rules apply both to employees working exclusively on the basis of a mini-job as well as to those holding a mini-job as a second job (additional to a regular job). For the new form of midi-jobs the limits of monthly remuneration are 401 and 800 €. Within this “gliding zone” (Gleitzone) social security contributions rise gradually from low to regular levels.

- Fixed-term employment: Since the mid-1980s (Beschäftigungsförderungs-gesetz - Employment Promotion Law) the maximum duration of fixed-term contracts without an objective cause has been successively extended from originally six months to nowadays two years. Deviations are possible by collective agreements. In the German legal context this form has to be distinguished from agency work.

- Agency work: The Hartz Laws resulted in its far-reaching deregulation. They removed the maximum length of assignment (Höchstdauer der Überlassung), formerly limited to two years, the ban on synchronization of the employment and the work contract (Synchronisationsverbot), as well as the ban on reassignment (Wiedereinstellungsverbot). In return, the principle of “equal pay for equal work” was introduced. Collective agreements are allowed to deviate from this general rule.

- Self-employment: The Hartz Laws introduced a new form of solo-self-employment, the so-called Ich-AG/Familien-AG (one person business/family business or Me, Inc. and family company) to be subsidized for a maximum duration of three years. This additional form of start-up grant was temporarily limited and terminated in August 2006. It was merged with the similar, more traditional instrument of so-called bridging allowances (Überbrückungsgeld) to a new, unified subsidy scheme for start-ups (Existenzgründungszuschuss). The opportunities for self-employment (Selbständigkeit) were broadened, to create additional employment.

These steps of deregulation broadened the scope of flexible labor input. Part-time and marginal employment, mini- as well as midi-jobs, extended the room of manoeuvre for internal-temporal flexibility, fixed-term and agency work broadened the opportunities for external-numerical flexibility. On the one hand, original fears that deregulation introduced since the mid-1980s would lead to a massive expansion of fixed-term employment proved unfounded. On the other hand, original hopes that deregulation would lead to a significant increase in employment have also not materialized.

Flexibility

The basic argument is that, in times of more competitive pressures, the potentials of flexibility can be increased to a considerable degree by introducing and extending atypical forms. Flexibility has often been reduced to the indicator of employment protection legislation (EPL) introduced by OECD (1994). This indicator is too narrow and lacks important dimensions. Various forms fit, first of all, specific objectives of management and companies, especially cost saving and efficiency needs. The choice between heterogeneous forms is primarily determined by performance goals management intends to achieve. This does not necessarily exclude employees’ interests in certain forms, particularly in flexible working time arrangements.

One basic distinction frequently applied in contemporary analysis is between internal and external forms, i.e. those without or with access to the external market. National labor markets differ according to their legal-institutional peculiarities: In Germany the internal version has been more frequently used and is more important (Herzog-Stein 2010, Möller 2010) whereas in the UK and the US the external one is more appropriate.

The sub-distinction, less widely spread, can be traced back to an early proposal by Atkinson (1984), later adapted by the OECD (1986). This fairly elaborate categorization distinguishes numerical, functional and wage (or more comprehensive monetary) flexibility. This distinction was, however, exclusively developed for normal employment and, therefore, needs to be broadened and adapted to cover also atypical forms. Internal “temporal flexibility” provides an additional category. This matrix refers primarily to dependent employment but we include pseudo self-employment (as a sub-category of solo-self-employment).

The application and combination of these distinctions enable us to clarify the relationship between specific, enterprise specific needs of flexibility (or adaptability) and the selection of atypical forms of employment. This choice is determined by the relative costs of individual forms. Among others, mini- and midi-jobs and part-time employment increase the degree of internal-temporal flexibility whereas temporary employment and agency work constitute typical forms of external-numerical flexibility (in cases of parental leave or project work or of unforeseen, short-term demand). External-numerical flexibility fits agency work and fixed-term employment and affects non-core workers but protects core workers against market fluctuations.

Fluctuations in agency work demonstrate the usefulness of our proposed distinction. With the onset of the economic crisis in mid 2008 the sharp increase agency work had experienced throughout the 2000s, was abruptly reversed (figure 1) and followed by an equally sharp decline. Since about mid 2009, when the recovery of the economy began, the figures have increased again and reached their all time peak. During the crisis many companies obviously made use of the fact that agency work constitutes a highly flexible form of employment. Agency workers can be quickly integrated into certain parts of the work organization, such as standard tasks that require only low skills. They can also be rapidly dropped without any redundancy costs.

Furthermore there has been a certain change in the function of agency work. Its original official task was to bridge unforeseeable gaps, among others in cases of sickness maternal leave, vacation or unexpected demand. More recently it has gained a certain strategic importance: Some companies use this form instead of normal employment (Seifert/Brehmer 2008, Holst 2010) in order to save wage costs, to increase their room of manoeuvre within HR and add another “flexible” segment to their internal labor market. For the time being the overall quantitative importance of this changed function seems to be limited.

5. Outlook

This article has demonstrated that forms of atypical employment have gained in importance over the last decades. These developments have, however, led to an increase of various, short-term as well as long-term social risks. These risks refer to the social situation of individuals, the overall labor market and the social security systems. Empirical analysis shows that they are different according to forms and their levels of precariousness.

The article has also provided some theoretical arguments to explain the expansion of atypical employment. These explanations seem to be incomplete due to the existing heterogeneity of forms and need to be elaborated. We proposed first steps.

References

Anger, C./Schmid, J. (2008), Gender Wage Gap und Familienpolitik, in: IW Trends 2, 55-68.

Atkinson, J. (1984), Flexibility, Uncertainty and Manpower Management, Brighton.

Baltes, K./Hense, A. (2006), Weiterbildung als Fahrschein aus der Zone der Prekarität, Berlin (working paper 4 des Rats für Sozial- und Wirtschaftsdaten).

Bellmann, L./Fischer, G./Hohendanner, C. (2009), Betriebliche Dynamik und Flexibilität auf dem deutschen Arbeitsmarkt, in: Möller/J., Walwei, U. (eds.), Handbuch Arbeitsmarkt 2009, Nürnberg, 360-401.

Boockmann, B./ Hagen, T. (2006), Befristete Beschäftigungsverhältnisse – Brücken in den Arbeitsmarkt oder Instrumente der Segmentierung?, Baden-Baden.

Brehmer, W./ Seifert, H. (2008), Sind atypische Beschäftigungsverhältnisse prekär? Eine empirische Analyse sozialer Risiken, in: Zeitschrift für Arbeitsmarktforschung 41, 501-531.

Brenke, K. (2008), Leiharbeit breitet sich rasant aus, in: DIW-Wochenbericht 19, 242-252.

Brenke, K. (2011), Ongoing change in the structure of part-time employment. DIW Economic Bulletin 6.2011.

Bundesagentur für Arbeit (2010), Der Arbeitsmarkt in Deutschland – aktuelle Entwicklungen in der Zeitarbeit, Nürnberg.

Dörre, K. (2006), Prekäre Arbeit. Unsichere Beschäftigungsverhältnisse und ihre sozialen Folgen, in: Arbeit 15, 181-193.

Esping-Andersen, G. (1990), The three worlds of welfare capitalism, Princeton.

Destatis (2008), Atypische Beschäftigung auf dem deutschen Arbeitsmarkt, Wiesbaden.

Destatis (2010), F1, Reihe 4.1.1, Wiesbaden.

Destatis (2011), F1, Reihe 4.1.1, Wiesbaden.

Fuller, S. (2009), Investigating longitudinal dimensions of precarious employment. Conceptual and practical issues, in: Vosko, L./MacDonald, M./Campbell, I. (eds.), Gender and the contours of precarious employment, New York, 226-239.

Gensicke, M./Herzog-Stein, A./Seifert, H./Tschersich, M. (2010), Einmal atypisch – immer atypisch beschäftigt? Mobilitätsprozesse atypischer und normaler Arbeitsverhältnisse im Vergleich, in: WSI-Mitteilungen 63, 179-187.

Giesecke, J./Gross, M. (2007), Flexibilisierung durch Befristung. Empirische Analysen zu den Folgen befristeter Beschäftigung, in: Keller, B./Seifert, H. (eds.), Atypische Beschäftigung – Flexibilisierung und soziale Risiken, Berlin, 83-106.

Herzog-Stein, A./Seifert, H. (2010), Der Arbeitsmarkt in der Großen Rezession – Bewährte Strategien in neuen Formen, in: WSI-Mitteilungen 63, 551-559.

Hohendanner, C. (2010), Unsichere Zeiten, unsichere Verträge?, in: IAB-Kurzbericht 14, Nürnberg.

Holst, H. (2010), “Die Flexibilität unbezahlter Zeit” – die strategische Nutzung von Leiharbeit, in: Arbeit 19, 164-177.

Houseman, S.N. (2001), Why employers use flexible staffing arrangements: Evidence form an establishment survey, ILRReview 55, 149-170.

Houseman, S.N./Osawa, M. (eds.) (2003), Nonstandard work in developed countries. Causes and consequences, Kalamazoo.

Japan Institute for Employment Policy and Training (JILPT) (2011), Non-regular employment – Issues and challenges common to the major developed countries. JILPT Report No 10, Tokyo.

Kalleberg, A. (2000), Nonstandard employment relations: Part-time, temporary and contract work, Annual Review of Sociology 26, 341-365.

Kalleberg, A. (2009), Presidential Address: Precarious work, insecure workers: Employment relations in transition, in: American Sociological Review 74, 1-22.

Keller, B./Seifert, H. (eds.) (2007), Atypische Beschäftigung. Flexibilisierung und soziale Risiken, Berlin.

Keller, B./Seifert, H. (2011), Atypische Beschäftigung und soziale Risiken. Entwicklung, Strukturen, Regulierung, Bonn.

Kvasnicka, M. (2008), Does Temporary Help Work Provide a Stepping Stone to Regular Employment? NBER Discussion Paper w13843, Cambridge.

Möller, J.(2010), The German labour market response in the world recession – de-mystifying a miracle, in: Zeitschrift für Arbeitsmarktforschung 42, 325-336.

Möller, J./Walwei, U./Koch, S./Kupka, P./Steinke, J. (2009), Fünf Jahre SGB II. Eine IAB-Bilanz. Der Arbeitsmarkt hat profitiert, IAB-Kurzbericht 29, Nürnberg.

Mückenberger, U. (1985), Die Krise des Normalarbeitsverhältnisses – hat das Arbeitsrecht noch Zukunft?, in: Zeitschrift für Sozialreform 31, 415-434, 457-475.

Mückenberger, U. (2007), Folgerungen aus der Krise des Normalarbeitsverhält-nisses, in: Lorenz, F./Schneider, G. (Hg.), Ende der Normalarbeit? Mehr Solidarität statt weniger Sicherheit – Zukunft betrieblicher Interessenvertretung, Hamburg, 80-109.

Neubäumer, R./Tretter, D. (2008), Mehr atypische Beschäftigung aus theoretischer Sicht, in: Industrielle Beziehungen 15, 256-278.

Nienhüser, W. (2007), Betriebliche Beschäftigungsstrategien und atypische Arbeitsverhältnisse, in: Keller, B./Seifert, H. (Hg.), Atypische Beschäftigung. Flexibilisierung und soziale Risiken, Berlin, 45-65.

OECD (1986), Flexibility in the labor market. The current debate, Paris.

OECD (1994), Employment outlook, Paris.

Osterman, P./Burton, M.D. (2005), Ports and ladders. The nature and relevance of internal labor markets in a changing world, in: Ackroyd, St./ Batt, R./ Thompson, P./ Tolbert, P,M. (eds), The Oxford handbook of work and organization, Oxford, 425-445.

Puch, K. (2008), Zeitarbeit. Ergebnisse des Mikrozensus, http://www.destatis.de/jetspeed/portal/cms/Sites/destatis/Internet/DE/Content/Publikationen/ STATmagazin/Arbeitsmarkt/2008__3/PDF2008__3,property=file.pdf

Reinowski, E./Sauermann, J. (2008), Hat die Befristung von Arbeitsverträgen einen Einfluss auf die berufliche Weiterbildung geringqualifiziert beschäftigter Personen?, in: Zeitschrift für Arbeitsmarktforschung 41, 489-499.

Rodgers, G./Rodgers, J. (eds.) (1989), Precarious jobs in labour market regulation: The growth of atypical employment in Western Europe. International Institute for Labour, Geneva.

Schmid, G./Protsch, P. (2009), Wandel der Erwerbsformen in Deutschland und Europa. Discussion Paper SP I 2009-505, Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin für Sozialforschung.

Sczesny, C./Schmidt, S./Schulte, H./Dross, P. (2008), Zeitarbeit in Nordrhein-Westfalen. Strukturen, Einsatzstrategien, Entgelte, Endbericht, Dortmund.

Seifert, H./Brehmer, W. (2008), Leiharbeit: Funktionswandel einer flexiblen Beschäftigungsform, in: WSI-Mitteilungen 61, 335-341.

Sesselmeier, W. (2007), (De)Stabilisierung der Arbeitsmarktsegmentation? Überlegungen zur Theorie atypischer Beschäftigung, in: Keller,B./Seifert,H. (Hg.), Atypische Beschäftigung. Flexibilisierung und soziale Risiken, Berlin, 67-80.

Standing, G. (2011), The precariat. The new dangerous class, London.

Vosko, L./MacDonald, M./Campbell, I. (eds.) (2009), Gender and the contours of precarious employment, New York.

Vosko, L. (2010), Managing the Margins: Gender, Citizenship and the International Regulation of Precarious Employment, Oxford.

Wolf, E. (2003), What Hampers Part-Time work. An Empirical Analysis of Wages, Hours Restrictions and Employment from a Dutch-German Perspective, ZEW Economic Studies 18, Mannheim.